Porte Cailhau – the Barbican of Bygone Bordeaux

11/10/2018

Brexit in Bordeaux – Outreach Meeting

26/10/2018100 Years Past: Traces of the American Landing in Gironde

To mark the 100th anniversary of the end of WWI, Bordeaux Expats and Sud Ouest take an in depth-look at Bordeaux’s pivotal role in winning the war – with the arrival of the Americans

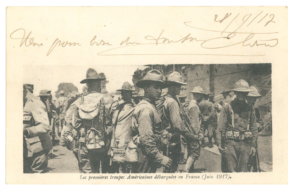

It’s a century since the United States entered the war in 1917 alongside the Allies, and the “Sammies” landed en-masse in Bordeaux. To mark the occasion, there has been a huge revival of interest in the hidden traces of the American settlement in the Sud Ouest.

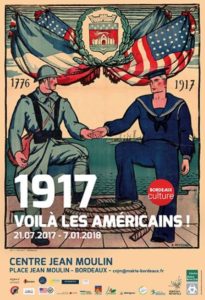

Last year, there was an exhibition at the Jean-Moulin center near Pey Berland called 1917 Voilà les Américains. It included talks and debates on subjects as diverse as –

The logistics of the American army in Gironde in 1917-1919: power, modernity and heritage

1917 – Jazz has arrived!

And 1917. The year that changed the world

USA-Bordeaux relations: the background

Bordeaux has a long-standing ‘special relationship’ with the United States. It has the oldest US consulate in Europe (the Hotel Fenwick at 1 cours Xavier Arnozanat Thomas near the quais), Jefferson visited the city and the Marquis de La Fayette left France for his first trip to the American coast from Bordeaux in 1777, three years before his famous crossing on board L’Hermione.

A forgotten history

Despite the monumental and war-changing presence of ‘Uncle Sam’s soldiers’ in Gironde, studies into their history and critical influence on WW1 have largely been sidelined.

The Sud Ouest was a long way from the front, and the troops stationed here were essentially in charge of the logistics and stewardship of the army. They built the colossal port, shifted thousands of tons of heavy equipment, and covered everything that was out of sight of the widely-reported front lines. Nevertheless, Bordeaux played a fundamental role in the war effort.

All-encompassing logistical support

In the final year of WWI, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) developed a comprehensive support network appropriate for the huge size of the American force. It rested upon the Services of Supply in the rear areas, with ports, railroads, depots, schools, maintenance facilities, bakeries, clothing repair shops (termed salvage), replacement depots, ice plants, and a wide variety of other activities.

The AEF initiated support techniques that would last well into the Cold War including forward maintenance, field cooking, graves registration (mortuary affairs), host nation support, motor transport, and morale services. The work of the logisticians enabled the success of the AEF and contributed to the emergence of the American Army as a modern fighting force.

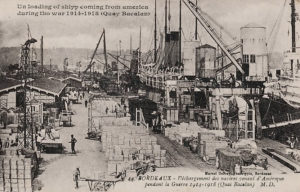

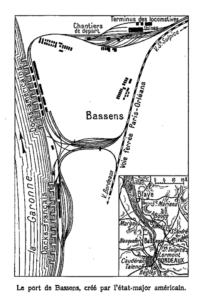

2.8 million tons through Bassens

Today, it’s hard to imagine the colossal deployment of equipment and men (more than a million soldiers) involved in the American Expeditionary Force’s engagement in France.

In 1918, 2 800 000 tons of equipment and goods were reported to have transited through the port of Bassens. In October 1918, day and night, an average of 7 men, 2 horses and 7 tons of equipment landed every minute. 1,500 steam locomotives and 23,000 wagons were provided by the United States, most of which were left behind at the end of the hostilities. This railway equipment was used for many years after the Great War.

Tens of thousands of soldiers set up home in the local region, accompanied by several thousand civilians supporting them through humanitarian associations. In Gironde, on 1 October 1918, the American workforce comprised: 3,202 officers, 89,027 troops, 4,366 civilians, and 168 nurses. They lived in a wide spectrum of military bases, most of which were dismantled when they left – see below.

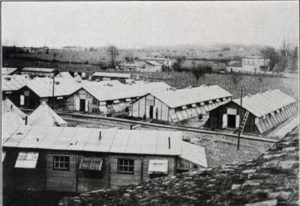

Army logistics divisions constructed vast camps of several hundred huts throughout Gironde, sometimes with rooms that could accommodate 600 people at a time – such as the Victory Theatre in Lormont-Génicart – most of them made of wood.

The Bordeaux region was specifically home to the army Supply Service, known as Base Section 2, which, in addition to focusing on the logistics of the American war effort, served as a behind-the-lines base network for the wounded and those on leave from the front.

Base Section 2 built field hospitals of unprecedented size around Bordeaux – particularly in Mérignac-Beaudésert, or installed them in pre-existing buildings, such as Château Trompeloup in Pauillac, the Petit Lycée de Talence, etc.

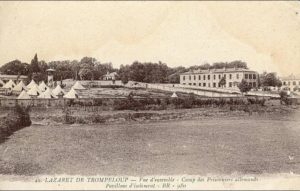

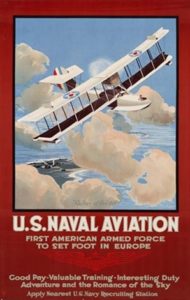

Pauillac Trompeloup served as a major maritime base with over 3000 men stationed there in 1918 – covering a range of activities such as the unloading, assembly and repair of all US Army seaplanes in service in Europe, as well as a station for a squadron of seaplanes participating in the surveillance of the Gascony coast.

Graffiti carved in stone: America’s lasting presence

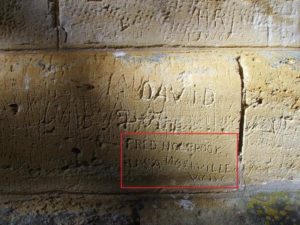

The American military was keen to erase all lasting traces from France’s landscape and society following the war – simply to restore “freedom and democracy for the peoples under the yoke of the German oppressor”. So the majority of American settlements were dismantled following the departure of the expeditionary force – after more than a hundred years, their trace has almost vanished completely.

However, a few links to the past remain today…

The Bassens quayside is one of the most remarkable achievements of the US presence in Bordeaux. Over 5 months, US forces built several hundred meters of wharves and tens of kilometers of rail track to enable ships from across the Atlantic to land the equipment and supplies needed to deploy troops. These facilities (since renovated or modified), served as the foundation for the modern port. Graffiti carved by American soldiers and dated 1918 is still visible on the quay.

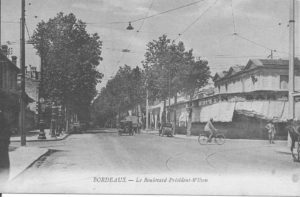

In Bordeaux itself, boulevard de Caudéran was renamed on July 13, 1918 in honour of President Wilson.

While, in Gradignan, there are traces of an ‘American fountain’ hidden under a heap of brambles. It marks the spot where the horses assigned to the troops came to drink in the Eau Bourde, the small river that crosses Bordeaux.

The Talence American Cemetery, created in April 1918, contains the graves of 13 Canadian and 5 American soldiers.

And in Villenave d’Ornon, the Bagatelle Florence Nightingale Nursing School, built in 1921, houses a commemorative stone in honour of American nurses who devoted themselves to caring for soldiers wounded from the front.

At Le Verdon-sur-mer, at the tip of the Médoc, there used to be a large monument erected to the glory of the US troops in 1938. The Germans unfortunately blew it to smithereens with dynamite in 1942, but the memories remain in the archives.

The American beach at Cap Ferret still exists, but the wooden hangars that prepared the seaplanes involved in the conflict built by the Navy regiments in 1917, have vanished without a trace. The construction of seaplanes in the region did not end in 1918 though – to find out more about this extraordinary regional history, head to the Hydraviation museum in Biscarosse.

Franco-American echoes

There were nearly 180 Franco-American marriages in Bordeaux between 1918 and 1920 – despite the challenges posed by the quasi-alcohol ban in the city! There were also many ‘adoptions’, which often consisted of the sponsorship of French orphans by American committees, such as those of the American Red Cross, to financially assist children whose fathers had fallen at the front.

The Americans also left their mark on French society by importing the US culture to Gironde. Through sport, their humanitarian approach, the management of troops and war victims – and music…

Enter American Jazz!

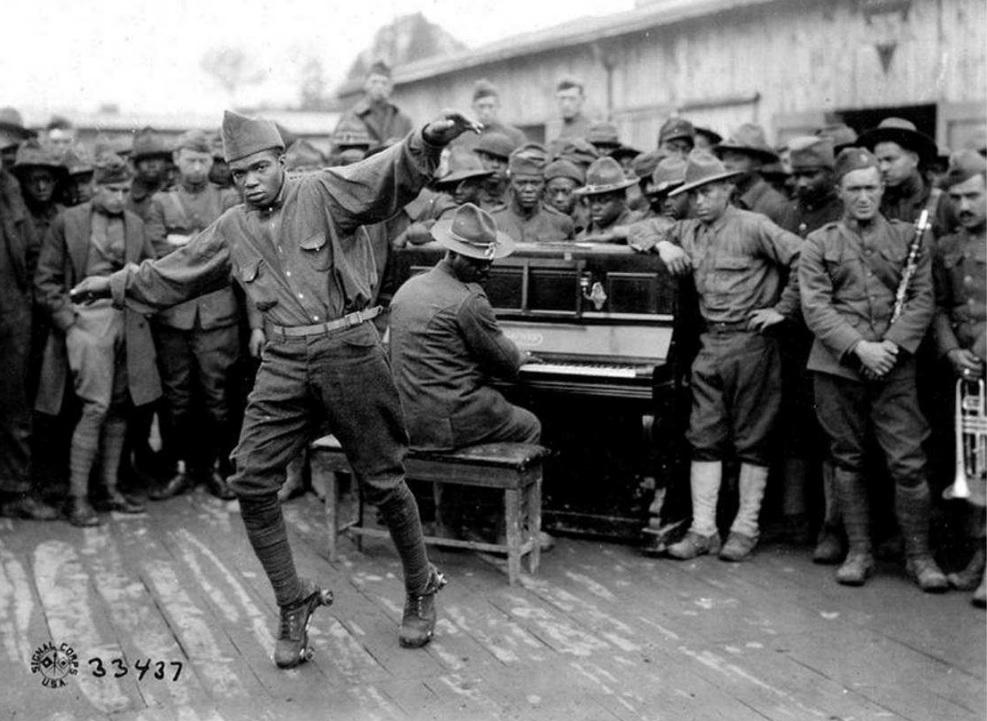

The first notes of jazz resounded as soon as the troops (and the Harlem Hellfighters!) arrived in 1917.

Of the 100,000 US troops that set up camp around Bordeaux, 20,000 were African American. Often forbidden to fight, they worked in support roles, such as building the port at Bassens – and they played jazz, or more specifically, ragtime!

Several bands that were extremely well known on the American scene came to Europe to play.

One of the very first jazz concerts in France took place in Bordeaux – courtesy of the 808th Stevedore Regiment.

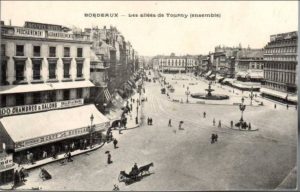

Several concerts by African-American lieutenant, bandleader and pianist James Reese Europewere also held in the Gironde capital. The concerts at the Café Anglais, on the Allées de Tourny became “an unmissable event for many Bordeaux residents”!

Black Americans were the object of great curiosity for locals at the time, and jazz was seen as the forbidden fruit of freedom and peace. It appeared at the same time in the other major French ports where American troops transited, Nantes and Brest.

After the war, the taste of jazz remained in Bordeaux in various bars frequented by young people and sailors around Saint-Pierre, where they listened to imported records, and in some theatres such as Le Français and Le Trianon. However, because of the Depression, and American protectionism, it only really took off properly after the Second World War.

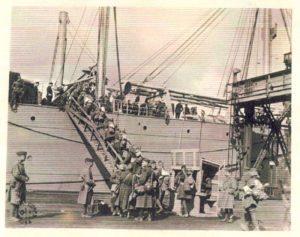

Home time

The American forces began their huge withdrawal operation following the armistice in 1918. Between November 1918 and July 1919, over 400,000 men set sail from Bassens or Pauillac Trompeloup (for the sick, convalescent or injured). This was accompanied by the dismantling of the logistical support bases. The Americans had made their indelible stamp on the history of Bordeaux.

Here’s a list of the American installations in Gironde in 1918

Base n°2 including the Bassens port facilities, the Saint-Sulpice d’Izon warehouses, the Saint-Loubès ammunition depot

Pauillac-Trompeloup Maritime Base

Souges Instruction Camp

Camps at Bassens, Carbon-Blanc (including a horse camp), Lormont (Génicart) for passing troops, and Cenon (Grangeneuve).

Courneau camp (near La Teste) for artillery

Seaplane station in Cap-Ferret

Airship station in Gujan-Mestras

Aviation School at Moutchic

Croix-d’Hins radio station

Hospitals in Talence and Mérignac (Beaudésert: planned capacity of 20,000 beds)

Troop depots in Libourne for heavy artillery

Coutras Store

Fuel depots (gasoline) in Saint-Loubès, Blaye and La Roque-de-Thau (Gauriac)

Centre for Permissionaires in Arcachon

Lift depot (supply of horses) in Mérignac (Beaudésert)

Postal center in Bordeaux (near Saint-Jean station)

Logging in the Landes de Gascogne

Administrative Services

Soldier assistance associations (American Red Cross, YMCA, Knights of Columbus)

Uniform and shoe repair shops

Warehouses

Garages in Bordeaux or in the inner suburbs (Gradignan, Bègles…)

Industrial installations requisitioned in June 1917 such as the quarries of Rions, Saint-Emilion, Montagne, Frontenac, Barsac, Lagrave d’Ambarès, Castres, Cadaujac whose materials were used for road services and the construction of the port of Bassens.

The Headquarters was located in the premises of the Faculty of Medicine, Place Victoire.

And those they left behind…!

Guard Camp: fallow and cultivated land, barracks (wooden with tarred paper cover) for 60 men, messes and latrines (16)

Camp Ancona-Baranquine: fallow and cultivated land

American Docks Headquarters: cultivated land

Camp Vinehard: cultivation area

Hill Camp: various terrains

Engine reception facilities: industrial sites

Soap plant: two buildings (with corrugated iron walls and roofing, cement paving), boiler and 40 HP steam engine (18)

Mechanical bakery: corrugated iron warehouse and bakery, four ovens, a mechanical mixer to produce 48 tonnes of bread per day, messes, kitchens and wooden latrines

Pump station in the north: makeshift hangar housing a boiler and a motor-pump unit

Prisoner of War camp: mess, reading room, prison (capacity of 380 men)

Ship repair workshop: building with 42 machine tools

A.T.S. Camp: wooden huts, laundries, messes, kitchens and various premises (total capacity of 600 men)

Repair shop for locomotives: various barracks, wooden tank

Camp Brohoist: 200-man barracks

Navy Hospital: wooden boats (capacity of 150 beds)

Fire station: corrugated iron huts

French Docks Station: sheet metal shack and repair workshop

Road service: equipment depot, stable and tool storage

Salvage Camp: wooden mess huts, kitchen, laundry room and latrines

Pump station near Salvage Camp: barracks with an electric pump and a pump with a petrol engine

Refrigeration plant: warehouse with a surface area of 7000 m2, premises and equipment for the operation of the plant

Elevating plant

Electrical plant

Coal handling facilities

De-greasing plant

Chinese Gunpowder Factory Camp (colonial workers’ camp)